Continued from Coming Out, Part Two: Albatross

VIII. Alaska

A couple months after I left the band, my father received a phone call from his sister, Patsy. Patsy had opened a small business—part convenience store, part diner—in the tiny town of Chitina, Alaska. She was about to build a church and needed help. She thought I might like to volunteer. A few weeks later, I boarded a plane for the first time in my life.

I still remember the flight: the glitter of cities below, the cold, indiscernible nothingness of Canada, and then Alaska, where the stars were interrupted by unyielding twilight, where the clouds broke into gargantuan mountains. Half an hour before touchdown, I pulled out my journal. “I will not let you go until you bless me,” I wrote, borrowing from the story of Jacob wrestling the angel. I needed answers. I had come to Alaska to wrestle with God.

I worked the convenience store the first month and waited tables the second. Some days, I helped the construction workers at the sanctuary, putting up drywall, insulating the attic, and painting the ceilings. True to plan, I did plenty of wrestling. On my solitary excursions to the church, I prayed for long hours, walking the parameter of the building, moving to the piano to worship. One evening in particular, my pleading got loud. Later that night, back at the diner, a construction worker caught me by myself. “You thought you were alone at church today, but I was in the back room,” he said. “That was intense.” I nodded and walked away, too embarrassed to reply.

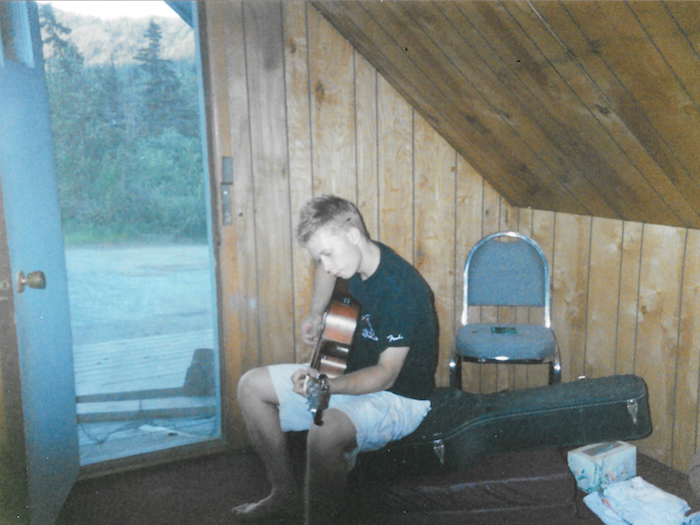

Halfway through my stay in Chitina, my cousin Randall joined us. A year younger than me and equally passionate about music, Randall and I spent our time together on instruments. I taught him the basics of songwriting, and he introduced me to new artists. Our bonding experience, especially over music, made me miss the Perrys.

At some point, that familiar longing to talk began to overcome me, so I decided to open up to Randall. We were in the work truck, making a trip for water, when I initiated a conversation that was becoming painfully familiar: “There’s something I’d like to tell you, but I don’t know how.”

“What is it?”

“It’ll freak you out.”

“Just say it, man.”

“I’m afraid to say it.”

To spare me the trouble, he started guessing. “Did ya kill someone?”

“No.”

“Steal somethin’?”

“No.”

“D’you do drugs?”

“Nope.”

“I don’t know, man. Am I even close? Just tell me.”

Silence.

“Do ya like guys?”

“No.”

“Girls?”

“I lied. You guessed it.” I felt sick.

“You like guys?”

“Yeah.”

Silence again. I waited for him to jump out of the truck. Instead, he put the vehicle in drive, and we made the trip back to the general store. “I may not agree with it, but nothin’s gonna change the way I feel about you, man.” That’s all he ever said about it. We continued on, singing and horse-playing, just the way we had before.

During my last week in Chitina, I wandered around the top of a mountain to take in the view. Something was different. My feelings about guys hadn’t changed. I didn’t have any answers. But for the first time in a long time, I felt peace. I had finally told someone.

v. Exodus: A Lapse in Judgment

During his second term as chairman of Exodus, John Paulk was spotted at Mr. P’s, a gay bar in DC. When asked about it later, he claimed he was just in to use the restroom. Patrons began to speak out, revealing that Paulk had been at the bar for over an hour, flirting with men. Shortly after the incident, his chairman status was revoked by the board.

Paulk apologized in a public statement: “My intentions were innocent, but my actions were unwise. The situation constituted a lapse in judgment, not a lapse in heterosexuality.”

Exodus put together a list of conditions that would allow Paulk to stay on as a member with probationary status. “John has demonstrated genuine remorse over his behavior and the negative impact that it has had on the credibility of Exodus,” wrote Bob Davies. “He is deeply committed to his wife and children.”

Years later, Focus on the Family’s James Dobson received a letter from a thirteen year old boy named Mark. Mark had written Dobson to seek counsel about his homosexual inclinations: “I’m afraid if I am not straight… I will go to hell. I don’t want to be not straight. I love God and want to go to heaven. If something is wrong with me, I want to get rid of it.”

Dobson published the letter and his response in his book Bringing Up Boys:

There are eight hundred known former gay and lesbian individuals today who have escaped from the homosexual lifestyle and found wholeness in their newfound heterosexuality. One such individual is my co-worker at Focus on the Family, John Paulk, who has devoted his life to caring for and assisting those who want to change.… Despite a momentary setback when he entered and was discovered in a homosexual bar, which delighted his critics, John did not return to his former life.

IX. Breaking Through

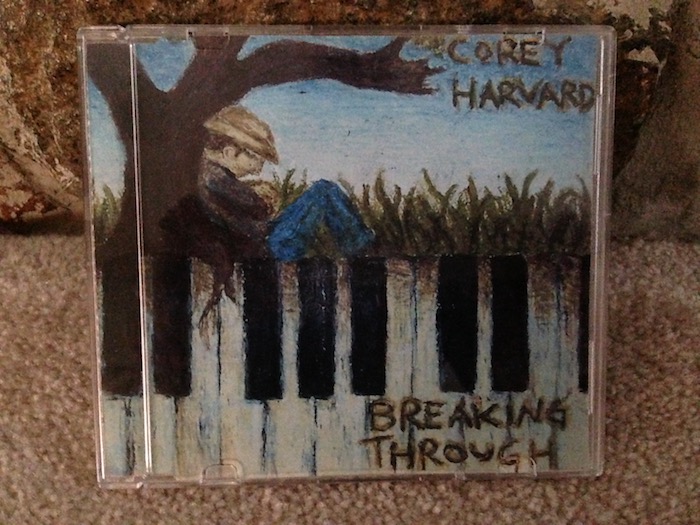

I was seventeen when I began taking songwriting more seriously. I wrote five or six songs before leaving for Alaska and at least six more within the first three months of my return. Excited at having written enough songs for an album, I pieced them together on a sixteen track recorder and called the project Breaking Through.

As my interest in songwriting grew, so did my desire for companionship. On long trips with my parents, I would lie in the back seat of the truck, close my eyes, and fantasize about making memories with another person. I pictured myself taking them on picnics, on hikes, to the arcade. I imagined holding them while they cried and taking care of them while they were sick. Whenever I snapped out of these reveries, I realized that the other person was always a boy. My spirit would sink, knowing that what I longed for and what I believed in were at odds, and that I’d never compromise the latter for the former. Those bittersweet daydreams inspired me to write “Near,” the first song I ever wrote about being gay.

After graduating high school, I went to work with my dad, a commercial fisherman. We’d leave the dock at some god-awful hour—3:30, 4am—and steer the Southbound into the pitch-black Gulf of Mexico. The further we got from shore, the brighter the stars became. On some nights, the wake around the boat would glow. The scientific term for the glow is bioluminescence, but the commercial fishermen called the glow “fire.” On nights we could barely see the moon, dad would call me to the wheel. “See that,” he’d say, “the water’s firing real good tonight.” When the boat passed over a school of fish, neon streaks of light shot in every direction like an underwater fireworks display. Those nights on my father’s boat were the closest I ever felt to God.

X. Soteriological Crisis

Coincidently, my father’s boat is also where my fundamentalism began to fall apart. I can remember the night it happened. Just days earlier, my friend Kierstin was telling me about a Catholic boy to whom she had grown close. “He’s just like you, Cor. Your age, your temperament.” Like the other kids I went to church with, I had been taught that Catholics had important misconceptions about scripture, misconceptions that could jeopardize their salvation.

Lying on the rumbling engine box of the boat, I stared at the stars, lost in thought. It occurred to me that I had never questioned my beliefs. I had been challenged before, no doubt, but as far back as I could remember, I had always started from the assumption that Christian fundamentalism is right; all information was interpreted through the lens of that assumption. I had never truly opened up to the possibility that my theology could be wrong.

Which led me to wonder: what if I had grown up in that Catholic boy’s family with the same genuine love of scripture and God? Would I be any less passionate a Catholic as I was a Protestant, any less sure that I was right and “they” (the Protestants) were wrong? What if I had grown up an eighteenth century Puritan? Or an Eastern Orthodox in the Middle Ages? Would I be damned for eternity because I wasn’t lucky enough to be born in a time or place that incubated and promoted the right beliefs? Did this seem consistent with the God Jesus describes in the gospels? The dominos began to fall.

XI. GCN

I first stumbled upon gaychristian.net (GCN) while doing research on the ex-gay movement. At the time I joined, the community was a few hundred members strong. GCNers fell on every point of political and religious spectrums: conservative and liberal, orthodox and emergent, Catholic and Protestant. Many participants were church leaders and seminary students; many more were recovering from years of reparative therapy.

On a page titled “The Great Debate,” GCN founder Justin Lee and his friend Ron Belgau posted two different Scripturally-based perspectives about homosexuality: Side A, that God blesses same-sex relationships; and Side B, that gay Christians are called to celibacy. GCNers used these categories—Side A and Side B—as identifiers and as a way to talk about their personal convictions. Unlike other ministries targeting gay people, this one wasn’t trying to make anybody straight.

I spent evenings poring over the GCN forum, asking questions, discussing scripture. Over time, I made friends, some of whom I talked with on the phone. Even Justin Lee called me up. GCN was my first safe space. No matter how turbulent life felt, I knew that there was a community of people waiting to receive me exactly as I was. The liberation that came along with being transparent on GCN made me realize that it was time to start telling people the truth.

Continue to Coming Out, Part Four: Bellow.

Amazing story. I love the way you write, and anxiously await the next part/chapter.

Corey Harvard you truly are an inspiration. I too cannot wait to read the next chapter. Love you. Xoxo