I. Boyhood

“Wake up, Jacob, kindle up a light if you wanna see Corey in a polecat fight!”

This was the jingle that dad woke me with every morning, and it was always accompanied by a ruckus: a squeaking cabinet door, a busy toothbrush, the clanking of coffee mugs, the hiss of a frying pan. Haggling with dad for extra sleep was pointless. But on the mornings he left early for work, I routinely begged my mother for “five more minutes,” and she routinely gave in. Unlike dad, mom approached the early hours with expert gentleness, closing cupboards softly, running faucets at a quarter turn. She woke me with a kiss on the forehead.

Like most families in small town Alabama, we were churchgoers. Mom made sure I was involved in Christmas pageants and Vacation Bible School. As soon as I was old enough to carry a tune, I was singing in front of the congregation. But far more important to me than performing at church was the idea of God: that He loved me, that He wanted to be a part of my life, and that I could be a part of His.

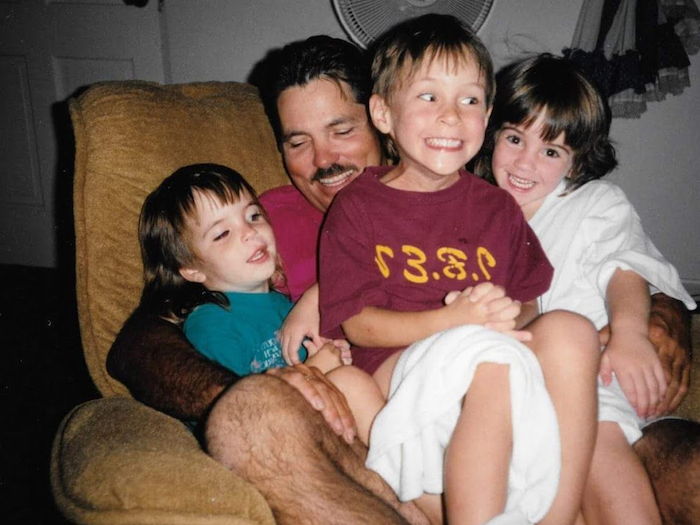

My favorite memories of those early years were evenings at the dining room table. The three of us took turns saying grace, a ceremony that dad initiated by setting his calloused, open hands on the table for us to grab hold. Dad began every prayer with “Humble our hearts, dear Lord, for these and all our many blessings.” Table talk usually involved dad’s workday or mom’s involvement at church. Dad fielded any questions that I threw at him. As the evening drew on, my father’s wit emerged, leaving mom and I laughing until our cheeks hurt and our eyes burned with tears.

By most measures, the 90s were peaceful years for me. I did well in school, I was active at church, and I lived in a structured household with parents who loved me. “An ideal childhood,” one might think.

II. Middle School

In middle school, I discovered songwriting. After Sunday morning services, I’d sneak over to the church piano and bang out pleasant nonsense. I kept at it long enough that my folks bought me a full-sized keyboard. The gift changed my life. I would hammer away at those keys for hours. Once I got the hang of it, I began writing songs.

At school, my Bible was always visible—on the desk, the cafeteria table, my hip. Classmates started calling me Preacher Boy. I attended “Prayer at the Pole” and weekly Christian club meetings. At home, I locked myself in my room and put on worship albums. I remember waking up at odd hours of the night, putting on my headphones, and crawling out of bed to pray.

It was locker room talk after gym class that made me realize I was different. “Did you see her boobs?” one of the boys shouted, cupping his chest. The others snickered. I didn’t get it. Even the more modest guys talked about girls. “What do you think about Jessica?” “She’s nice,” I would reply, knowing that I wasn’t quite answering the question.

Of course, I was going through the same strange metamorphosis as the rest of my class. Most of the changes were easy to recognize: peach fuzz, alto voices free-falling into baritone. But then there was attraction, something imperceivable but very real. And unlike those other changes that were apparent and awkward, whenever attraction happened, it happened so subtly that you couldn’t remember what it was like not to experience it.

Perhaps that’s why in sixth grade, I didn’t spend much thought on my attraction to other boys. When I daydreamed about a crush, it felt natural. It wasn’t until some point between seventh and eighth grade that I began to think: this isn’t going to be okay.

i. Conversion Therapy

“How does a gay person become straight?” I wasn’t the first gay teenager to research the question, a question that invariably leads to the story of conversion therapy.

The concept was first propagated by a variety of psychologists in the mid-20th century. There were as many ideas about the cause of homosexuality—unhealthy parent-child dynamic, sexual abuse, and narcissism to list a few—as there were “cures.” Some psychologists used psychoanalysis in attempt to correct unresolved childhood conflicts, others showed their patients homoerotic images while injecting them with nausea-inducing substances.

Psychologists boasted about the efficacy of their treatments until time and research revealed that, in addition to being grossly ineffective, conversion therapy was damaging the people it was supposed to cure. In 1973, the American Psychological Association (APA) declassified homosexuality as a mental disorder.

III. Mobile Music Machine

In eighth grade, I won the Grand Bay Middle School talent show with an original song. I finally had something to show for two tireless years of piano-playing and lyric-writing. Around that same time, my pediatrician, Dr. Steve Perry, was looking for musicians. His daughter Kimberly was already at the helm of a local Christian band. Feeling that his sons were old enough to have a band of their own, Dr. Perry asked my mother if I’d be interested in joining them as a keyboardist. For the next several months, I met with the Perry boys and two other recruits to practice at the doctor’s office after operating hours. We called ourselves the “Mobile Music Machine.”

I loved band practices, and not just because I was passionate about music. In my bandmates, I found a camaraderie that I never found at school. The Perry boys were gentle souls with big imaginations. When we weren’t learning songs, we were citizens of Middle-earth, wielding swords, fighting orcs, reenacting scenes from Lord of the Rings. In a way, my time with the band felt like a fantasy in itself, a place separate from the real world where I didn’t have to think about what it meant that I was attracted to boys. I could hide in the music.

ii. Exodus: The Genesis

Three years after the APA removed homosexuality from the DSM, Exodus International was born. For over three decades, Exodus served as the largest organized Evangelical effort to cure homosexuality. Pastors could offer only prayer and support to the “same-sex-attracted;” the folks at Exodus offered a cure. When gay-rights activists argued that being gay isn’t a choice, Exodus published testimonials of members who were married with children.

So what did Exodus posit as the cause and cure for homosexuality? The same hypotheses and treatments of those psychologists of the past. Leaders of Exodus often recycled the theory that homosexuality resulted from having a distant father and overbearing mother. They reverted to the tenets of conversion therapy, pressing for confessions of childhood neglect while conditioning boys to act more masculine, girls more feminine. Treatment was garnished with prayer, Christian mentoring, and fellowship.

Exodus co-founders Michael Bussee and Gary Cooper were two of the earliest champions of the ex-gay movement. They took their message of deliverance from homosexuality across the country, claiming God had freed them from their same-sex attractions. They had the wives and children to prove it.

Continue to Coming Out, Part Two: Albatross.

Ugh..i want to keep reading!!! Even though i know your story, your writing sucks me in all over again!

Me too!!!! Love and miss you Corey!!!