Continued from Coming Out, Part Three: Water Fire

XII. Freshman Year

“I’m gay.”

One of the first people I came out to was a friend of the family named Kelly. Years prior, she sang in a gospel trio with my mother. She was both a professional counselor and a diligent researcher, which I figured were good enough reasons to confide in her. I sent her an email about it, and she replied the same day. “I had a hunch,” her email began. “You’re gonna be okay. Let’s figure it out together.”

Around this time, I began my first semester at the University of South Alabama. Since I’d been homeschooled, I hadn’t sat in a full classroom with other students for years. As I bounded across campus, I started to grapple with the same painful self-consciousness I endured in 9th grade. I hated my voice, my posture, and the nervous way I interacted with people. It felt like my awkwardness was the loudest thing in every room.

On the first day of an intro to psychology course, the professor had us introduce ourselves to the rest of the class. As my turn approached, my hands began to shake. We were supposed to share our names and one interesting thing about ourselves. “C-corey,” I stammered. “Alright, C-corey,” the professor teased, “What’s interesting about you?” My mind went blank. For six or seven mortifying seconds, I stared at the far edge of my desk, trying to think of something, terrified to look up. The back of my neck burned hot. “We’ll come back to you, sweetie,” the instructor finally said.

Between classes, I sprinted to the library to see if Kelly had left me any emails. Our messages were long and rambling: we discussed Scripture and circled around to the burning question of how to come out to my parents. In my free time, I logged on to the GCN forum to see how my friends around the country were holding up.

XIII. The Bookstore & Brandon

With a college schedule, I could no longer work with dad, so I got a job at Barnes & Noble (B&N). A couple months in, I discovered that my general manager was a devout Southern Baptist with strong convictions about gay people. At the end of a shift, she complained to me about an employee who had just come out. “I don’t know why he needs to dress like that,” she said frowning, referring to his skinny pants. She quieted her voice and looked at me over the top of her glasses: “You know, he didn’t always act this way.”

Then there was the floor manager, Jo. Jo was a fifty year old Buddhist with the grace of a dancer and the wisdom of a sage. She had an exuberance of spirit that spilled out into uncontainable laughter, deeply felt compassion, and a childlike capacity for awe. I was mystified by Jo. I came out to her soon after I got hired, and she became one of my fiercest allies.

Kelly, Jo, and the folks on GCN were all wellsprings of hope for me, but I still felt alienated from my peers. I wanted to talk to someone I could relate to, so I found a guy on Myspace who listed himself as “Gay” and “Christian,” and I asked him if he’d be willing to get together. A few evenings later, we met at B&N. The meeting was a bust. “How did you reconcile your faith with your sexuality,” I asked him. “I dunno,” he said shrugging, “I believe Jesus loves me.” He didn’t have anything else to say about it. “What was it like to come out?” I asked him. “It sucks. I’m sick of gays,” he responded, “The last two guys I dated are hooking up now.” He proceeded to tell me about the disaster that was his love life. It’s all he wanted to talk about. Feeling disappointed and a little uneasy, I asked him what kind of music he listened to. Surely there’s something we can connect over, I thought. “Acid rock,” he replied. Nope.

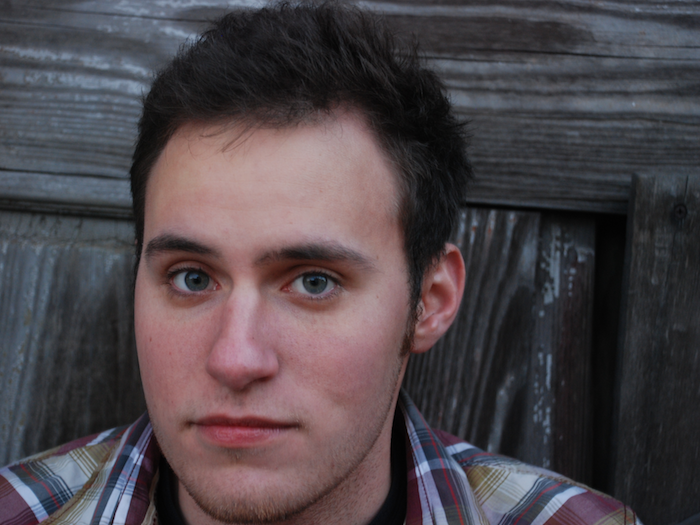

A couple weeks later, I received a Myspace message from a guy named Brandon. He had heard about me (word travels fast in the gay community) and decided to reach out. Our bond was immediate and easy. Usually, we met at night—at Waffle House, at the truck stop, or in a local park—and he listened to me ramble about everything. When we weren’t swapping stories about growing up gay in the south, we were brainstorming ideas to write fantasy novels (like all decent human beings, Brandon is a Tolkienite). Occasionally, I’d sneak through his bedroom window and we’d watch movies or listen to music together. Brandon was one of the few people who made me feel comfortable in my own skin.

Despite all the newfound support, my anxiety worsened. I was living two lives: the one my friends and family saw and the one confined to emails, an online forum, and discrete hangouts with Brandon. I worried about mom and dad. Living with them only intensified the conflict. It was becoming clear to me that I had to move out. In the months before I left, I recorded a song called “Sorry for Myself.” Unbeknownst to my parents, I had written it for them.

vi. Exodus: Apologies

In 2007, Michael Bussee, along with former Exodus leaders Jeremy Marks and Darlene Bogle, apologized for their work at Exodus International. In his apology, Bussee acknowledged that “not one of the hundreds of people counseled ever became straight.” He went on to talk about the damage of reparative therapy:

Many of our clients began to fall apart… One young man in our program got drunk and deliberately drove his car into a tree. Another fellow leader of the ex-gay movement told me that he had left Exodus and was now going to straight bars looking for guys to beat him up. He explained that the beatings made him feel less guilty. He was atoning for his sin.

Six years later, in a letter to PQ Monthly, former Exodus chairman John Paulk would follow suit. “Today, I do not consider myself ‘ex-gay’ and I no longer support or promote the movement. Please allow me to be clear: I do not believe that reparative therapy changes sexual orientation; in fact, it does great harm to many people.”

XIV. No Man’s Land

During the second semester of my freshman year, I came out to my apologetics buddy Mike. He didn’t see it coming, but supported me all the same. I was looking at apartments with a mutual friend of ours—Scott—around the time that I told him. “I should probably tell Scott before we live together,” I told Mike. He agreed.

The three of us were eating dinner when I decided to broach the subject. I looked over at Mike, second-guessing myself. “Corey’s gay,” he announced, wasting no words. Scott seemed surprised. After he had time to digest the news, I asked him if he was still comfortable with the idea of living with me. “Yeah man, of course,” he replied. A few months later, we moved into Knollwood Apartments.

I met Emily on a night shift at B&N. Emily was a philosophy and economics major at Springhill College. In a matter of weeks, she became one of my closest friends. We would meet across the street from my apartment at Cottage Hill Park where the two of us would stay up late talking about books and philosophy. After she read one of my poems in Oracle, the University of South Alabama’s fine arts review, she confronted me in an aisle at B&N. “Are you gay?” she asked. A line in the poem had tipped her off. I stood there, momentarily flummoxed. It was the first time someone had asked me that. “Yeah, I am.”

The rate at which I was coming out was disorienting to me. On one hand, being seen and accepted felt liberating. On the other, openly identifying as gay heightened a sense of urgency in me, urgency to tell my parents and urgency to iron out the tenets of my spirituality. But the task felt insurmountable. I had continued the work I began on my father’s boat of deconstructing my childhood beliefs. Biblical authority, atonement theology, eternal punishment: nothing was spared examination. Questions led to more questions. I had wandered into a theological No Man’s Land, and I didn’t see a way out.

XV. Acquainted with the Night

I struggled to sleep. When sleep wouldn’t come, I slipped out to the park. I ate constantly, even when I wasn’t hungry. The money I didn’t spend on food went to buying music and books: anything to numb the anxiety.

Sleep deprivation led to nausea, which gave me an excuse to skip class. Just occasionally at first. Then for a whole day. Then for a week. When I finally walked into Geology 111, my stomach turned in knots as the professor passed out an exam on a section I’d completely missed, much less studied. I handed in a mostly-blank test and snuck out of the classroom. My grades plummeted. Eventually, I dropped all my classes.

I barely had enough money to put gas in the car, so I quit leaving the apartment. I only got out of bed to eat and use the restroom. Whenever I had to talk to people, I did my best to keep up the facade that everything was normal.

One evening, after I had finished hanging out with Mike, I sat listlessly in my room. I was tired. The thought of not existing felt like a relief. I opened up my bedroom window and perched on the sill.

Are you there? I prayed.

Nothing. I felt nothing.

I was losing everything that mattered. I hadn’t just given up the band: I’d given up on my best friends and the career of my dreams. I was failing at college. And as far as I could tell, God had turned his back on me. The project of my youth; the enormous love and energy I had put into my relationship with God; the years I had foreclosed on my romantic desires to follow Christ—it was all in vain. I was alone.

What happened next has always been a blur. I remember frantically putting on shoes. I remember running out the front door, down the steps, across the apartment complex. A car horn blared as I sprinted across the road. I remember that the street lights looked like porous balls of fuzz and the wet grass squeaked beneath my sneakers. I ran till I couldn’t breathe. And then I bellowed. I wailed until my throat burned raw. I did it for the naive kid I’d been, who went to school with a Bible at his hip. I did it for Preacher Boy.

I have no clue how long it lasted. I do remember that everything was spinning when Mike and Emily found me. Mike could tell something was wrong when he visited earlier that day, so he had come back to check on me. When I didn’t answer the door, he called Emily. They decided to search the park. When they spotted me, Emily ran the rest of the way, and I collapsed into her arms sobbing.

Eventually, exhaustion set in. We slowly made our way back to the apartment, where the three of us crawled into my bed and fell asleep.

Continue to Coming Out, Part Five: Home.

“Acquainted with the Night” is the title of a poem by Robert Frost.

The featured photo was taken by Brandon Boykin, and the shots of me with Brandon and Emily were taken by John Coons.

Here are the full apologies of former Exodus leaders Michael Bussee, Jeremy Marks, and Darlene Bogle:

Thanks for writing this Corey. We’ve anxiously awaited each new part.

Thanks for following along, Craig.

This is so beautiful written Corey. It touches a deep part of my soul, causing me to look inside and check myself for other deeply rooted but false beliefs that I’ve somehow missed. I know this life is all about the journey but I find myself impatient for all the revelations to come. Thank you for all you’ve done to change my own life. Reading this is like sitting in front of the fire on a cold night with a good friend. I’m looking forward to the next one. I love you!

brother.

Corey, your coming out story is so powerful and beautiful and well written. I know that it will touch people’s lives. Thank you so much for sharing your musical gifts at Open Table. You are such a blessing! Ann